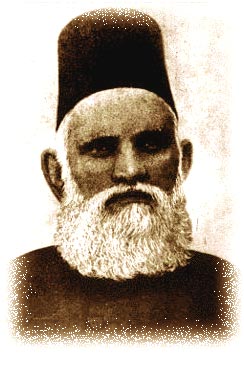

나와브 모신 울 물크

Nawab Mohsin-ul-Mulk

|

나와브 모신 울 물크 (Nawab Mohsin-ul-Mulk) 1837-1907 [파키스탄의

역사]

1867년에 그는 주공무원 (Provincial Civil Service) 시험에서 수석을 차지하여 UP의 부세금원(deputy collector)로 임명되었다. 이때부터 그는 사이드 경(Sir Syed)이라고 알려지기 시작했다. 1874년 메디 알리는 하이더라바드(Hyderabad)로 진출하였고 하이더라바드의 니잠(nizam, 군주)은 그의 공헌을 기리도록 “무니르 나와즈 장(Munir Nawaz Jang)”, “나와브 모신우드돌라(Nawab Moshin-ud Daula)”라는 칭호를 주었다. 1893년 메디 알리는 알리가(Aligarh)에 와서 사이드 아마드 칸 경을 도와 알리가의 메시지를 전파하는 일을 하게 되었다. 그는 사이드 경이 작고한 후 무슬림 교육협회(Muslim Educational Conference)의 책임자가 되었다. 20세기를 맞이할 즈음, “United Province"에 힌디-우르두 간의 논쟁이 격화되었다. 그는 우르두 보호 협회(Urdu Defense Association)를 도와서 우르두를 변호하는 글을 썼다. 그는 또한 멀리 내다보는 통찰력을 가지고 정치적으로도 의식이 있는 리더였다. 그는 영국총독의 개인 비서와 편지를 주고 받으며 모든 의회, 지방단체에도 무슬림을 대표할 수 있는 독립적인 대표가 필요하다는 그의 견해를 피력하였다. 1906년 그는 나와브 비까르울물크와 함께 무슬림리그의 정관을 초안하도록 요청받았다. 당뇨로 오랫동안 고생하던 그는 1907년 11월 16일에 사망하였다. [reference] Indian nationalism

and the British response Nationalism in the Muslim community While the Congress was calling for swaraj in Calcutta, the Muslim League held its first meeting in Dacca. Though the Muslim quarter of India's population lagged behind the Hindu majority in uniting to articulate nationalist political demands, Islam had, since the founding of the Delhi sultanate in 1206, provided Indian Muslims with sufficient doctrinal mortar to unite them as a separate religious community. The era of effective Mughal rule (c. 1556-1707), moreover, gave India's Muslims a sense of martial and administrative superiority to, as well as separation from, the Hindu majority. In 1857 the last of the Mughal emperors had served as a rallying symbol for many mutineers, and in the wake of the mutiny most Britons placed the burden of blame for its inception upon the Muslim community. Sir Sayyid Ahmad Khan (1817-98), India's greatest 19th-century Muslim leader, succeeded, in his “Causes of the Indian Revolt” (1873), in convincing many British officials that Hindus were primarily to blame for the mutiny. Sayyid had entered the company's service in 1838 and was the leader of Muslim India's emulative mainstream of political reform. He visited Oxford in 1874 and returned to found the Anglo-Muhammadan Oriental College (now Aligarh Muslim University) at Aligarh in 1875. It was India's first centre of Islamic and Western higher education, with instruction given in English and modeled after Oxford. Aligarh became the intellectual cradle of the Muslim League and Pakistan. Sayyid Mahdi Ali, popularly known by his title Mohsin al-Mulk (1837-1907), had succeeded Sayyid Ahmad as leader and convened a deputation of some 36 Muslim leaders, headed by the Aga Khan III, that in 1906 called upon Lord Minto (viceroy from 1905 to 1910) to articulate the special national interests of India's Muslim community. Minto promised that any reforms enacted by his government would safeguard the separate interests of the Muslim community. Separate Muslim electorates, formally inaugurated by the Indian Councils Act of 1909, were thus vouchsafed by viceregal fiat in 1906. Encouraged by the concession, the Aga Khan's deputation issued an expanded call during the first meeting of the Muslim League (convened in December 1906 at Dacca) “to protect and advance the political rights and interests of Mussalmans of India.” Other resolutions moved at its first meeting expressed Muslim “loyalty to the British government,” support for the Bengal partition, and condemnation of the boycott movement.

Morley's major reform scheme, the Indian Councils Act of 1909 (popularly called the Minto-Morley Reforms), directly introduced the elective principle to Indian legislative council membership. Though the initial electorate was a minuscule minority of Indians enfranchised by property ownership and education, in 1910 some 135 elected Indian representatives took their seats as members of legislative councils throughout British India. The act of 1909 also increased the maximum additional membership of the Supreme Council from 16 (to which it had been raised by the Councils Act of 1892) to 60. In the provincial councils of Bombay, Bengal, and Madras, which had been created in 1861, the permissible total membership had been raised to 20 by the act of 1892, and this was increased in 1909 to 50, a majority of whom were to be nonofficials; the number of council members in other provinces was similarly increased. In abolishing the official majorities of provincial legislatures, Morley was following the advice of Gokhale and other liberal Congress leaders, such as Romesh Chunder Dutt (1848-1909), and overriding the bitter opposition of not only the ICS but also his own viceroy and council. Viceroy Morley believed, as did many other British Liberal politicians, that the only justification for British rule over India was to bequeath to the government of India Britain's greatest political institution, parliamentary government. Minto and his officials in Calcutta and Shimla did succeed in watering down the reforms by writing stringent regulations for their implementation and insisting upon the retention of executive veto power over all legislation. Elected members of the new councils were empowered, nevertheless, to engage in spontaneous supplementary questioning, as well as in formal debate with the executive concerning the annual budget. Members were also permitted to introduce legislative proposals of their own. Gokhale took immediate advantage of these vital new parliamentary procedures by introducing a measure for free and compulsory elementary education throughout British India. Although defeated, it was brought back again and again by Gokhale, who used the platform of the government's highest council of state as a sounding board for nationalist demands. Before the act of 1909, as Gokhale told fellow members of the Congress in Madras that year, Indian nationalists had been engaged in agitation “from outside,” but “from now,” he said, they would be “engaged in what might be called responsible association with the administration.” Copyright ⓒ 1994-2002 Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. |

| 파키스탄 개요 | 역사 | 경제 | 결혼식 | 기후 | 토막정보 | 방명록 |